Delighting Without Asking: A Behavioral Science POV on Customer Experience

Editor’s note: This is a chapter from the ebook, Unlock the Value of CX. You can download the entire book here.

As marketers and CX professionals, we care a lot about what our customers think. No opinion matters more than theirs. So, we often ask them for it. “What did you think about this? Did you enjoy that? Which would you prefer? Please choose, please rank, please describe…”

What if I told you that most of the time… people have no idea? That’s a theme that is consistently emerging from the field of behavioral science. We think we know what we want, but the truth is, the neural mechanisms and ingrained biases driving our decisions lie far beneath the layer of consciousness accessible to us when articulating our experiences or predicting our choices.

Thinking Fast vs.Thinking Slow

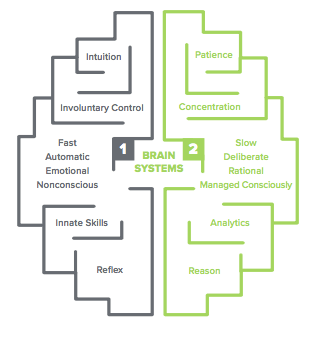

I’m talking about the emotional brain, versus the rational brain. The elephant controlling the rider. The System One process versus the System Two. In his book inking Fast and Slow,1 Nobel-prize winning behavioral economist, Daniel Kahneman establishes two parallel processes by which our brains make sense of the world and our experience within it. System One is fast, automatic, emotional, and nonconscious. System Two is slow, deliberate, rational, and “managed” consciously. Because we are consciously aware only of System Two, we genuinely feel that everything we do is governed by rational thought. We are unaware of the many hidden motivators and cognitive “shortcuts” our System One uses to make the vast majority of our decisions swiftly and automatically, in the interest of freeing up our cognitive energy for life’s more complicated decisions.

Cognitive Heuristics

There are many fascinating examples of these cognitive shortcuts, otherwise known as biases or heuristics. Perhaps the best known is the power of the default setting, made famous by its effect on organ donation in Johnson and Goldstein’s landmark 2003 study.2 The decision of whether or not to enlist as an organ donor, one would think, is both intimate and fraught with personal and cultural values. It turns out, however, that the main determinant of whether or not an individual enlists as an organ donor, is whether their governing body offers this as a default “opt-in”or “opt-out” choice. At the time of the study, Germany’s “opt-in” setting led 12 percent of their population to enlist as a donor, while neighboring, and culturally similar, Austria’s “opt-out” default seing led almost 100 percent of its citizens to choose to remain in the donor pool. In the US, by the way, 85 percent of citizens say they want to be organ donors, but only 28 percent actually are. This could be due to our country’s opt-in default setting. What’s interesting about the power of defaults is that we rationally deny their effect on our decisions. Citizens of the aforementioned countries rationalize their choices to be a donor or not, based on personal or cultural values. They don’t think about the default setting. Companies use defaults all the time: automakers display vehicles fully loaded, and it’s up to us to deselect each delightful feature, feeling the pain of loss with each “uncheck”.

Another prevalent cognitive bias is social proof. Take those placards in your hotel bathroom, for example, urging you to recycle your towel for the good of the environment. Sometimes they give you statistics on the millions of gallons of water saved when you choose to hang your towel on the hook to use another day. Behavioral science shows us that information like this doesn’t really change behavior. But social proof does. Noah Goldstein experimented with the towel placards by adding an element of social comparison. Indicating that “Most other people who stay in this hotel recycle their towels,”3 increased towel recycling by 26 percent. Amazingly, adding a layer of specificity to an arbitrary “in-group,” “Most other people who stay in this room recycle their towels,” increased recycling another seven percent! We are indeed a social species. The leading customer engagement platform for utilities, Opower, leveraged this effect by issuing Home Energy Report letters,4 which compared each household’s energy usage to that of comparable neighbors. This social comparison caused recipients to decrease their energy usage by up to 6.3 percent among the highest energy users. Lotteries are another great example of cognitive bias in action. Though it makes little rational sense, humans predictably choose a 10 percent chance at winning $30 over a sure bet of three dollars.

Lab animals of nearly every species have been shown to display a preference for a lever that rewards them with a treat intermittently, or randomly, versus providing a certain reward. Companies employ the random reward effect with lotteries and sweepstakes, as effective drivers of customer engagement.

What’s so interesting about these biases is not just that they predictably drive our behavior, but that they do so in a way that is hidden to us. Disclosing a default setting, for example, though appreciated, does not affect the likelihood of choosing the default, because the default bias is driven by our System One “shortcut” process. Asking someone to predict or describe their behavior, calls on their System Two. Our mouth doesn’t always know what our heart is doing.

Seeing What’s Easiest to Explain

There are a few other important things to consider when asking people to articulate their choices and experiences. In his research on predicted utility, Christopher Hsee asked people to choose between a small chocolate heart and a large chocolate cockroach.5 ough only 46 percent actually preferred the cockroach, 68 percent chose it. It’s more chocolate after all, the reasoning goes, and it would be rationally foolish to leave chocolate on the table. When asked to make a choice, we often default to the most justifiable option—even when it’s not what we really want. Even more troubling, this effect can cause us to enjoy our experiences less. Researchers at the University of Virginia asked students to choose a free poster from a box.6 One random group of those students was asked to explain their choices. While most students preferred impressionistic painting posters, and chose to take those home when they weren’t asked to explain their rationale, the “explainer” group chose against their preference, instead taking home funny animal posters. They found the choice of animal poster easier to articulate, than the impressionistic paintings. Consequently, one month later, they were far less happy with their posters.

Even the way we collect information from customers influences their choices and behavior. Jonathan Levav found that when customers are specking a product such as a new car, the order in which the product attributes are presented, matters.7 Subjects were more likely to choose a default option after they had considered an attribute with many choices (e.g. paint color) first, than when the first decision was one with fewer choices (e.g. engine type). It may be that we only have so much energy to burn on System Two decision-making, before we give in to the default bias and accept what’s presented to us.

The point is this: we care about our customers, and must learn as much as we can about their needs, preferences, experiences, and desires. But asking them gives us only part of the story. Behavioral science gives us a peek beneath the layer of conscious awareness, and a reliable set of principles to use as we explore the creation of experiences that appeal to people holistically: through both their Systems One and Two.

SOURCES & NOTES

- Kahneman, Daniel. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow.

- Eric J., and Goldstein, Daniel G. “Do Defaults Save Lives?” Science Vol. 302. (2003): 1338-1339.

- Goldstein, Noah J., Cialdini, Robert B., and Grizkevicius, Vladas. “A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels.” Journal of Consumer Research Vol. 35. (2008).

- Allcott, Hunt. “Social Norms and Energy Conservation” Journal of Public Economics Vol. 95. Issues 9-10 (2011): 1082-1095.

- Hsee, Christopher K. “Value seeking and prediction-decision inconsistency: Why don’t people take what they predict they’ll like the most?” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review Vol. 6. Issue 4 (2011): 555-561.

- Wilson, Timothy D.; Lyle, Douglas J.; Schooler, Jonathan W.; Hodges, Sarah D; Klaaren, Kristen J.; LaFleur, Suzanne J. “Introspecting About Reasons Can Reduce Post-Choice Satisfaction” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol. 19. Issue 3 (1993): 331-339.

- Levav, Jonathan; Heitmann, Mark; Herrman, Andreas; and Iyengar, Sheena S. “Order in Product Customization Decisions: Evidence from Field Experiments” Journal of Political Economy Vol. 118. Issue 2 (2010): 274-299.